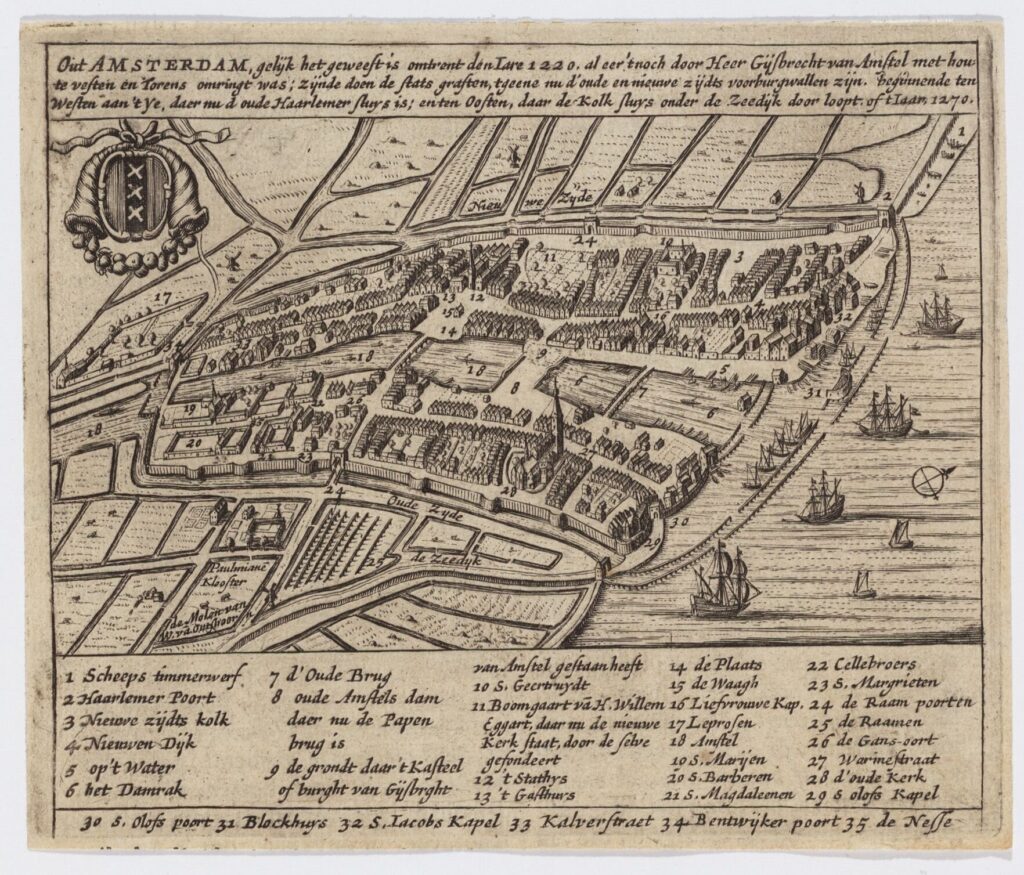

Today, 27th October, Amsterdam turns 750. I previously wrote a blog about how Count Floris V mentioned Amsterdam for the first time in his Toll Privilege, thereby “putting our city on the map.” In this context, I’m offering historical walking tours covering Amsterdam’s 750-year history. While researching this tour, I came across a city map by Marcus Willemsz. Doornik that is meant to depict the situation in 1220. What immediately struck me was the location of the Dam—at about where the Beursplein is situated today. Doornik describes it as: “old Amstel dam where the Papenbrug is now.” The Papenbrug was the southernmost of the three bridges over the Damrak until it was demolished in 1884. The alley from Beursplein to Warmoesstraat still reminds us of this: Papenbrugsteeg.

This map dates from around 1665 and is therefore not contemporary. Doornik depicts various buildings from a later era, such as the old city hall (after 1368) and the Old Church (from 1250). Yet it seems an interesting illustration of what the city may have looked like in the late Middle Ages—for example, the course of the Amstel, the canals, and the streets of that time.

In my research I came across several 17th-century examples of this representation, the oldest by Christoffel van Hartogvelt from 1613. Some mapmakers who seem to rely on the same model date the depicted situation not to 1220 but to 1400 (see the map at the top of this article).

What I’m wondering now is this: is this image of the Dam fanciful, or might the original dam have been moved? And if that happened, why? And are we celebrating that 750th anniversary—the mention of Amsterdam in Floris V’s Toll Privilege in the year 1275—in the wrong place?

I started my search with the historians and read Geert Mak’s A Brief History of Amsterdam. In his chapter on Amsterdam’s beginnings he refers to an earlier discussion among historians and archaeologists about dating the construction of the dam. Many historians rally around the year 1265, but archaeologists believe the dam was built in the first quarter of the 13th century. Mak adds: “The dam, …, was [according to recent research] laid across the Amstel shortly after the floods of 1170 and 1173.” He finds it logical that the dam would have been made at the same time as the construction of quays and dikes. Moreover, according to Mak the dam provided a necessary connection between the buildings on both sides of the Amstel—what we now call the Oudezijde (the Old Side) and the Nieuwezijde (the New Side).

Both sound plausible, but then I think: in the 12th century they already built bridges. But perhaps making a dam is easier than making a bridge?

Mak continues: “According to tradition, the crossing first lay closer to the IJ, roughly at the height of the Nieuwe Brug. By moving it further back, a natural harbor arose at the river’s mouth.” I find his choice of words for “tradition” interesting. So far I’ve found no other reference to this tradition. And he places the dam all the way at the mouth of the Amstel by the Nieuwe Brug, which still stands next to the Victoria Hotel. But the idea of “moving it back,” thereby creating a natural harbor, doesn’t seem illogical to me.

I also read a contribution by historian Ben Speet to the standard work History of Amsterdam about the construction of the dam: archaeologists who date the build to the early 13th century and historians who believe it must have been between 1265 and 1275. He concludes that “the conclusion has been drawn that between 1265 and 1275 a dam was laid in the river at the expense of the [Van] Amstels.” These Van Amstels are the famous Gijsbrecht IV and his brother Willem. Speet says nothing about a possible relocation.

Former city archaeologist Jerzy Gawronski argues in the 2017 Amstelodamum yearbook that 1266 is the most likely year for the construction of “a dam with sluices at the mouth by the Dam.” He is referring here to the dam sluices, which were only removed in the 20th century. He thus dates the construction almost in step with the historians. For his account he draws on the extensive archaeological research carried out in the 2000s during the construction of the North–South metro line, which he led. He arrives at the date 1266 on the basis of traces of scouring in the Amstel that could only have been caused by the discharge of large quantities of water through sluices. An un-dammed river flows too slowly for that; a dammed river doesn’t flow at all. Gawronski does not mention an earlier dam.

These historians and archaeologists make the date 1266 for the construction of the dam with sluices at the site of today’s Dam highly plausible. Yet this still leaves room for what Mak suggests: the existence of a dam that may have been built a century earlier. But does that make the 17th-century depictions of an Amsterdam with a dam at the location of today’s Beursplein more than flights of fancy?

And what can be said about the cartography? Marc Hameleers, the specialist in maps at the City Archives, describes in his excellent survey Maps of Amsterdam the various 17th-century city plans on which the Dam is situated at the site of the Papenbrug. He discusses details such as later-period buildings—for example the medieval city hall and the Old Church—but nowhere does he address the curious depiction of the Dam at the aforementioned location.

So what is my conclusion on the day Amsterdam celebrates its 750th birthday? Are we celebrating at the wrong dam on the Amstel the fact that Count Floris V in his famous Toll Privilege of 1275 mentioned “amestelledamme” for the first time? No, that doesn’t make sense. That dam must be the dam with sluices from the year 1266. But I still wonder how people got from the Old Side to the New Side until then.